Chronicles of La Ribera:

Memories from San Cristobal’s historical tithe ledger

By: María del Refugio Reynozo Medina

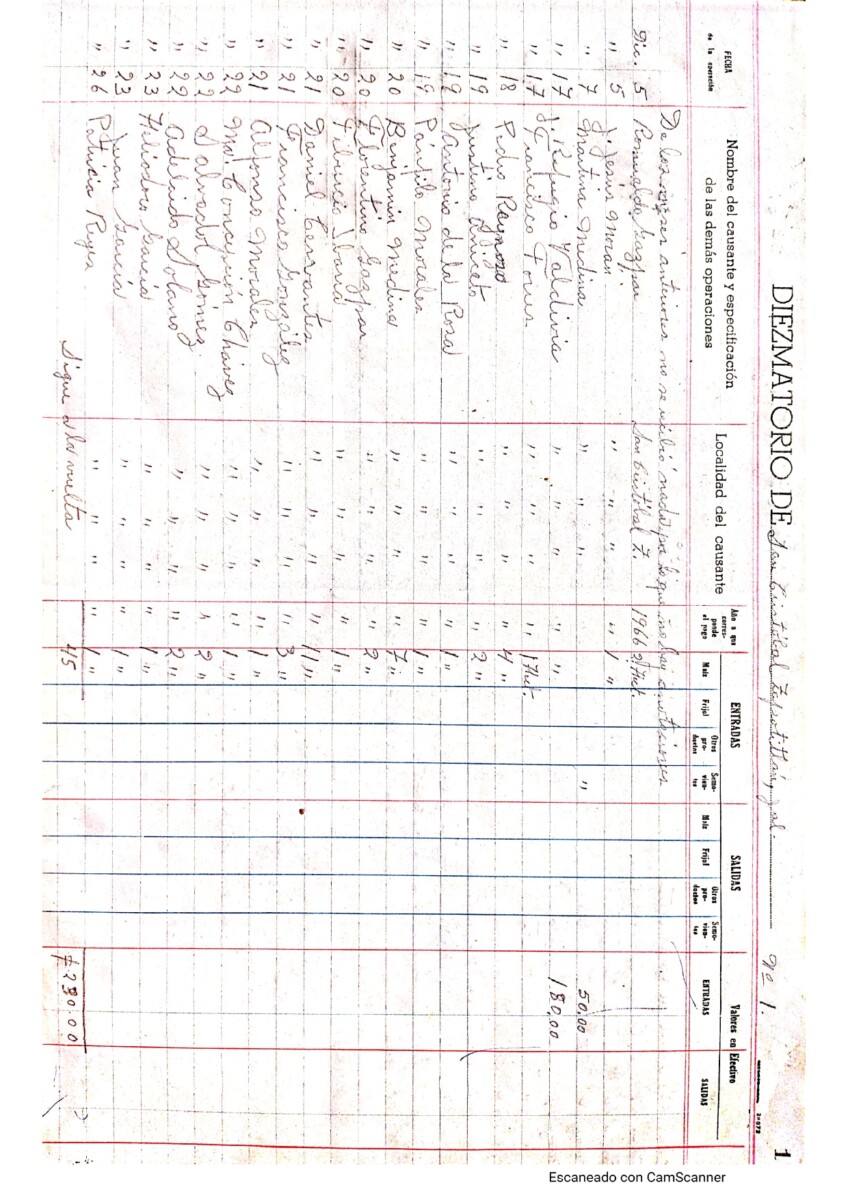

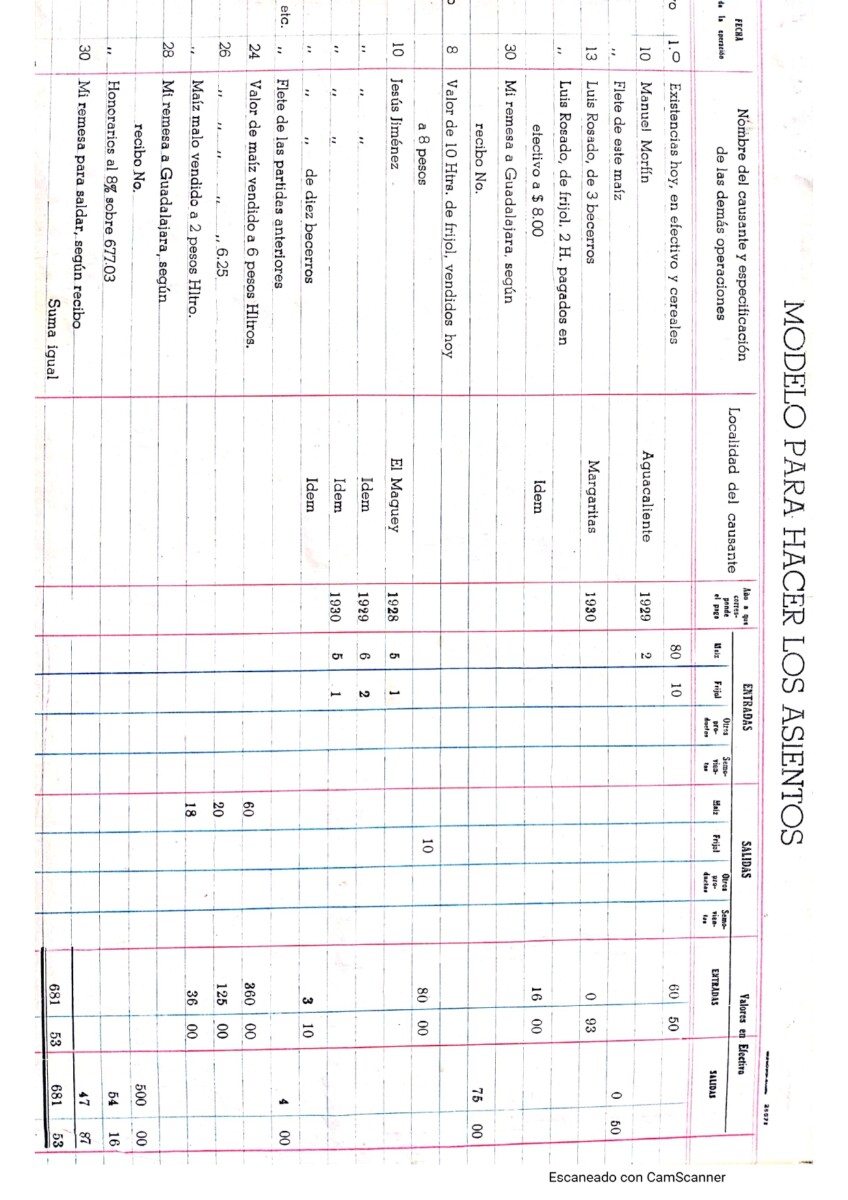

The original tithe ledger where the contributions pledged by the parishioners were recorded. Photo: María del Refugio Reynozo Medina. Courtesy Historical Archive of the parish of San Cristóbal Zapotitlán.

«Honor the LORD with your possessions and with the first fruits of all your produce,» so says the biblical quote from Proverbs 3:9.

Nena is 85 years old and her sister Consuelo is 95 years old. Consuelo remembers that since she was about five years old, her parents taught them the Catholic faith. Even before the temple was finished being constructed they would go to mass. She remembers that the children brought little buckets filled with donkey excrement and straw to make the traditional adobes on site. In those years there was a lot of excrement available to make adobe. Animals were allowed to go loose, walking, chewing the grass in the streets, getting between the fences.

The settlers not only contributed to the construction of the temple, whose exact date is unknown, but also to the ongoing support of the church through the tithe.

In the historical archives of the parish of San Cristobal Zapotitlán are the tithe ledgers, or the books where the income that the church received from the parishioners was recorded.

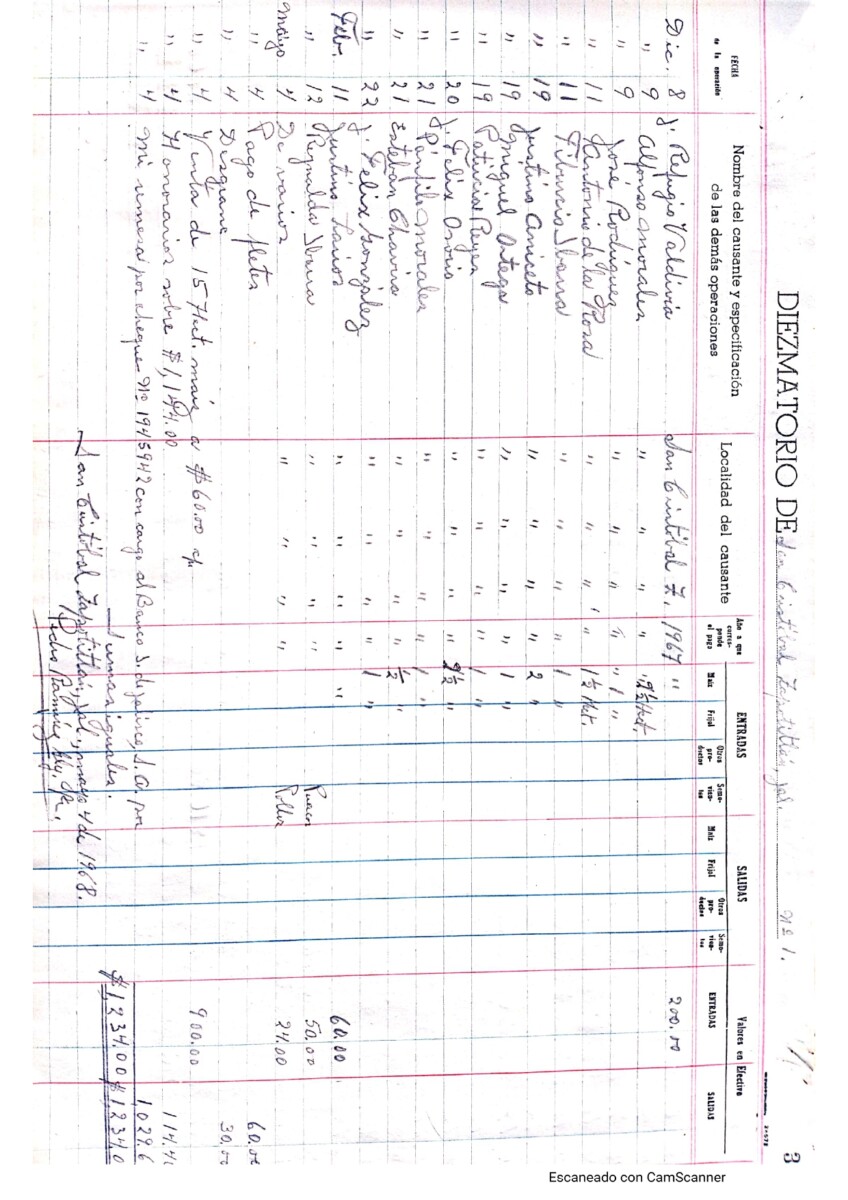

The tithe was commonly given from the fruit of the harvest, sometimes the offering was chickens, pigs or even eggs. In these historical records, which date from 1966 to 1970, the names and the number of loads of harvest that were given to the church appear (a load was about two sacks or “costales” as we know them today). The parish priest was Pedro Ramírez González. Nena remembers him, he was a tall, blue-eyed, laughing man.

-I remember my dad carrying a small load of corn from his land clearing for the tithe.

During the harvest months, you could see dozens of donkeys outside the temple unloading bags of grain, usually corn, sometimes chickpeas. Behind the temple, where Alcoholics Anonymous meetings are held today, there was a shed where they kept whatever was tithed.

The tithe was signed by the priest Pedro Ramírez González. Photo: María del Refugio Reynozo Medina. Courtesy Historical Archive of the parish of San Cristóbal Zapotitlán.

Nena remembers that some brought chickens. She would go out into the streets with a basket to collect eggs house by house for the improvements of the church, and also money for the priest’s allowance. Many chicken sellers came to the town.

-They would shout, «Gallinas que vendaaan!” “Chickens for sale!” They carried them on their shoulders holding them by their legs and others carried them by their fists like bunches.

In the historical archives appears a list of the names of the characters that existed, all of them now deceased, but alive in the memory of this 85-year-old woman.

One of the names is Florentino Gaspar pledging 2 loads of corn. He and Carmen Mosqueda were the owners of a store where they sold petroleum that was the fuel for the devices that illuminated the nights, because there was no electric energy. They kept it in big drums and the people came to get it in bottles.

They also sold the corn with which the women made the nixtamal, to later turn it into tortillas that they prepared every day on a stove and with a metate. The lard was sold in a rectangle of brown paper.

Another name that appears is that of Benjamín Medina, pledging 7 loads of corn.

Daniel Cervantes appears in the roster pledging 11 loads. He was a generous benefactor of the temple; Cervantes donated the images of the Sacred Heart and the full size Virgin Mary that he brought from Guadalajara and is still in the parish today. He and his sister Luz Cervantes sold a piece of land to contribute to the completion of the church.

The list goes on; Alfonso Morales, who pledged one load. He was the father of Julia Morales, the petite, dark-haired woman with the eternally smiling face in charge of the mail. Many women anxiously awaited her passage on the mail route.

It was said that on one occasion a suitor asked her if she wanted to be his girlfriend, and she replied, «Later.» She was asked again to know his answer, she said she meant later in another time. And she continued to deliver sighs from house to house.

-I haven’t received anything, Julia,» some of the women would plead.

Juanita remembers anxiously awaiting Julia’s arrival, because her husband was in the United States working and among the love letters came some US dollars.

Example of filling out the tithe. On the first page of the document. Photo: María del Refugio Reynozo Medina. Courtesy Historical Archive of the parish of San Cristóbal Zapotitlán.

Justino Larios, who also pledged a load, was a great musician, he played the clarinet. His sister Dominga Larios had the first telephone booth in town, the wooden booth was attached to the wall, it had a handle and keys to dial.

-San Cristóbal calling San Pedro,» the operator Dominga Larios would say.

She relayed many phone messages from the priest.

In the tithe list is also José Rodríguez who contributed a load. He was a bricklayer, almost the only one in those days. He made his houses all the same, a small room with a window and a corridor.

Esteban Chavira also appears in the record with the contribution of half a load, he did religious plays or ‘pastorelas’ in the street, he read the dialogues to the devil and to Gila who was another character.

One of the songs said:

-The Virgin was washing and St. Joseph was tending, the child was crying from the cold he had.

The rehearsals for the pastorelas were at night when the men and women finished their days under the protection of candles or oil lanterns. When someone wanted the shepherds to sing for them they would invite them and make them food, that was only at Christmas time.

Nena remembers that, in one procession to Jocotepec during the traditional January festivities of the Señor del Monte, Chavira made a float and took Victor Amezcua as Jesus Christ, the people even cried to see the character so real, they say that this photo was taken to Rome by a priest who came to visit and the people went on a pilgrimage to greet him at the crossroads.

Brígida Velasco, who pledged half a load, made very ornate wax candles, the ornaments stood out like a glow of the wax itself. Nena remembers a scene with Brígida holding the wick and letting the wax drip to form candles of all sizes. Brigida’s son was a hairdresser, they say that he used to splash water on his clients’ heads to prepare their hair for the haircut.

The drawn landscape of the San Cristóbal of yesteryear seeps through the memories of the men and women who lived it. Memories fade, but the names of those who existed are there in the documents, in the tithe lists that remain the mute witness of the inevitable passage of time.

Translated by Kerry Watson

Los comentarios están cerrados.

© 2016. Todos los derechos reservados. Semanario de la Ribera de Chapala