historia

Chapala president calls upon citizens to unite on 216th anniversary Benito Juárez’s Birthday

The president of Chapala, Alejandro de Jesús Aguirre Curiel, and local deputy, María Dolores López Jara offered a floral arrangement at the “Benemérito de las Américas” Credit: Jazmín Stengel

Editor (Chapala).– Chapala President Alejandro de Jesús Aguirre Curie called for citizens to unify in the municipality and leave divisions behind during the commemoration of the 216th anniversary of Benito Juárez’s birthday

«May the framework of this celebration for the 216th anniversary of the birth of Benito Juarez, be the perfect reason to overcome harsh divisions, and unite in favor of Chapala and Chapala residents.» Aguirre told the citizens, adding that, «The example of Benito Juarez should remind us of the principles of democracy, equality, tolerance, and respect – indispensable foundations of the rule of law of any nation.» At the event, students from the Eugenio Zúñiga elementary school provided a short history of the life of Benito Juarez, also known as “Benemérito de las Américas” or “deserving of the Americas’ praise.” Valentín Gómez Farías highlighted Juarez’s history of public service including: the governorship of Oaxaca, magistrate of the Supreme Court of the Nation. As president of Mexico, he is credited with major legal reforms.

Translated by Amy Esperanto

Caldo Michi: The dish of Lake Chapala’s fishermen

Caldo Michi often has potato and carrot

Sofia Medeles (Ajijic).– “Caldo Michi” or Michi Soup is a very traditional dish for many of the towns around Lake Chapala, and Ajijic is no exception. The former Director of the Historical Archive of Chapala and researcher, Eduardo Ramos Cordero, shares his memories of this traditional dish. According to his grandfather’s memories, the broth was prepared by fishermen after their day’s work. Back in the 1950s and even before, Ramos Cordero recalled that he observed this custom, not only during Lent, but on a daily basis, «Before, the shores of the lake were full of crops: peanuts, watermelons, melons, chili peppers, cucumbers, papaya, jicama, even marijuana and poppy. Some of the owners of these orchards did not pay with money, but in trade. The fishermen would agree that one or two would go to the shore of the lake to start preparing the soup, so that by 2-3 pm, everyone would be eating.»

What varied in the broth was mainly the type of fish used. The fishermen used everything from catfish, tilapia, carp, white fish, charales (chirostoma), to acociles (a tiny crayfish), red crab, small crabs, eels or lamprey fish and turtles. The original preparation includes a bit of lard, tomatillos, onion, plums or green mango (depending on the season), and chiles güeros or banana peppers. The veggies are sautéed, and then the water, fish, salt are added. It’s garnished with a few sprigs of flowered cilantro.

«I had nutrients from many fish,” said Eduardo Ramos Cordero. Known also as Lalo. “When the broth was made, everyone ate: the fishermen, their wives (who brought tortillas), and sometimes their children. Although it was originally made by fishermen, lots of others made it, especially during Lent,» Lalo finished.

Some sources say that this dish originated in the town of Atotonilco, Jalisco, however, for the most part, researchers have found a broth being prepared in a similar way throughout the Lake Chapala area. Its name comes from the Nahuatl word, Michi, which means fish, although others claim it’s because it comes from Michoacán.

Caldo Michi Recipe

Ingredients:

2T lard

4 tomatillos, cut in large wedges

1 onion cut into quarters

6 banana peppers, without tip

A sprig of flowered cilantro

4 medium catfish

Water

Salt, to taste

Optional: Depending on the season, ¼ of green plums, or 4 green mangoes peeled and split and pitted.

Directions

- Heat the lard in a large pot over medium, once it is melted and hot, sauté the tomatillos, onion, and chiles güeros.

- Add the water and let it boil.

- Add fish to taste, either whole or in pieces, salt to taste. Add water to cover the fish.

- As soon as the fish is cooked, remove from heat, garnish with cilantro.

Translated by Amy Esperanto

Lakeside Chronicles

Seño Cata doesn’t like pictures. ‘I am ugly,» she tells me. But her photograph contradicts her. Photo: María Reynozo.

María del Refugio Reynozo Medina

At 93 years old, Catalina Valencia Navarro walks around the house alone, leaning on a walker with an impeccable face. “I am very happy,» she says with a deep sigh.

She doesn’t need to say it, it is announced by her slow but sure steps, her beautiful luminous eyes and the gentle smile framed by her burnished hair. She wears black shoes that reveal her perfect toes, a long khaki A-line skirt and a soft almond-colored blouse.

Catalina Valencia retired at the age of 82 after 62 years as a teacher. “It’s a mistake to be in teaching if we don’t like it,» she said. In addition to being an elementary school teacher, she co-founded the Magdalena Cueva High School project in 1963 with the principal Antonia Palomares Peña. There she taught English and geography.

The first complete elementary school was started by Palomares because at that time in Jocotepec, elementary school was only up to fourth grade.

“The principal trusted me a lot, she was energetic and very prepared.”

“Cata» as her pupils called her, tells of her experiences with facts and names as if it were yesterday.

«The principal commissioned us to go all over town inviting the children house by house.” They also went to invite children in the towns of San Cristóbal, Zapotitán, Huejotitán and El Molino.

The first high school began in a borrowed building, the José Santana Elementary School. In the afternoon, after the elementary school children had finished their day, the older students attended school.

Mario González Barba taught biology and was the godfather of the first generation of students.

Priest Santiago Ramirez taught drawing and Engineer Jorge Ibarra Galvez taught chemistry.

It was a cooperative high school and the students paid 30 pesos a month. The teachers earned 15 pesos an hour if there was enough money to pay them. A board of trustees made up of people from the community managed the school and was transparent about the resources.

In 1970 the board of trustees managed to build a separate school with contributions from the efforts of the parents, the teachers, and the community, even the masons contributed their labor. The high school was a milestone in the history of Jocotepec. For many, there is a Jocotepec before the high school and Jocotepec after the high school.

In 1982, under the premise of the President of the Republic that there should be secondary schools all over the country, an authority came to Jocotepec to offer a secondary school. The municipal president at that time, responded that there was already a secondary school and allowed its appropriation for the creation of the official secondary school. That action stripped the school from the founding teachers. The teachers were fired. For Valencia Navarro and her colleagues, it was a repudiatory act. “I don’t even want to say the name of that authority because it still hurts me.»

As a high school teacher, something that always filled her with satisfaction was to see those children who, with so many difficulties, achieved their goal. Some students came from other communities, walking across the hill to get to school. The teachers adjusted the classes to the students’ schedules and even taught on Saturdays. Valencia Navarro recalls that a boy from Potrerillos would sleep in his friend’s garage so he could attend school.

«I loved the children from San Cristóbal very much because they were very noble, they left a beautiful mark on me.»

When Valencia Navarro retired, the high school had 300 students. She still remembers them.

“I don’t know if they loved me,» she says, «but many still visit me, and I love them.”

In 1987, «Seño Cata» (short for «Señorita» similar to «Ms.» or Missus) retired with 36 years of service in education. Her mission did not end there. A Zacatecan priest in San Juan Cosalá sought her out, Alberto Macías Llamas, who ran a boarding school. Valencia Navarro went for six months and stayed for 21 years serving the 200 children from rural communities.

Although Catalina was director, for her the most beautiful thing was not the important position, but the closeness with the children in the classroom as a teacher. «I always liked my students to be the first, never the last, and I would get the first places in the achievement contests.»

When I ask her to show me her awards, she agrees, but first says, “Wouldn’t it be a chocantería (impertinent)?”

We walk to the hallway where her degrees and awards hang. Those decorations and the recognition of her students are the most valuable things for her, although they are not proportional to the amount of the pension she receives.

«When I was a child, I saw my mother die. I stuttered and it wasn’t until I was nine years old that I overcame it and was accepted in elementary school.» The classroom was in what is now the Jocotepec municipal marketplace. «We were so poor in the town that we didn’t even have a school. One of the classrooms only had walls and no roof. Some teachers would take the children home and teach them there.» She remembers her teacher Felicitas Palomares with love; she was very important in her childhood. Perhaps that is why «seño Cata» is also a very dear teacher for her students.

If she were born again, she would be a teacher again.

Translated Nita Rudy

El espíritu de puedo ayudarte;

By Patrick O’Heffernan

While attending the LCS Annual Membership Meeting this week (by Zoom from the Semanario Laguna offices) I could not help being impressed by the almost unbelievable amount of activity the organization generates with its 300 volunteers, small staff and very energetic board. It operates or hosts over a 100 programs, including the Todos English program of expat volunteers here at Semanario Laguna who translate all of our Spanish stories into English each week.

Of course, LCS is only one of the many NPO’s (non-profits) in Lakeside. Lakeside Foodbank, Lakeside Little Theater, Niños Incapacitados , Cruz Roja, SOS Chapala DOG Rescue, Bare Stage and Bravo Theater, and many more. The Foundation for Lake Chapala Charities list 25 affiliated non profit organizations, but of course, there are many more that are not affiliated, and even some that are not registered as NPO’s, but still do great work without the imprimatur.

Nationally, the Mexican government reported 5,339 NPOs in the country 2003, but the Inter Press Service (IPS) has suggested that 10,000 NGOs actually exist in México. Mexican non-profits do everything from provide emergency food to families, to rescue dogs and horses, to provide shelter for battered women, to fight for human rights, to help poor families with medical care. In other words, they do everything needed in the country

That is what I call el espíritu de puedo ayudarte – ”the spirit of can I help you”. It is built into the culture.

But organized non-profits on a large scale are not built into Mexico’s history. A 2015 study by the Hauser Institute at the Harvard Kennedy School pointed out that the history of nonprofits in Mexico is relatively recent. Up until the 1880’s philanthropy was almost unknown outside of the Catholic Church. In the early 20th century secular organizations emerged to provide aid to the poor. These civil society organizations grew rapidly under the PRI, becoming almost synonymous with the political party.

But in the 1960s through the 1980’s, the independent non profit sector exploded, propelled by the 1968 student revolution, growing calls for social movements that addressed public needs, and finally the Mexico city earthquake in 1985. The ascent of the PAN party in 2000 opened up new space for nonprofits and they rushed into it.

Here in Lakeside, old timers tell me (since there is no Harvard study)that Neil James and the influx of Expats from the US with 501 (c)(3) (US nonprofit tax exemption) experience kicked off what has become a dense ecosystem of NPOs here.

One aspect of the NPO ecosystem in Lakeside that is important and possible somewhat unique is that it is a force that brings the Mexican and Extrañero communities together. At one level it is Expats working within Mexican communities to help, but at another, very wide level, it is joint Mexican-Expat boards and staffs solving problems together. And the nonprofit sector encourages conscious efforts to reach out, like the Mexican Advisory Board at LCS or Laguna’s Todos English translation team of Expats ( not a non-profit, we hope, but wonderful outreach).

I worked for many decades in and through non profits in the US and even founded a couple. In my experience, the presence of NPO’s in a community is a sign of economic strength, a healthy society, and the kind of heart that makes us good human beings. If you are part of a NPO, thank you; if not; join one. It will make you feel better and help us all. And you will love being part of the ecosystem of el espíritu de puedo ayudarte

Terranova Institute commemorates International Women’s Day

Terranova Institute students commemorated International Women’s Day by sharing examples and opinions regarding the violence they suffer throughout the country. Screen copy.

D.Arturo Ortega (Chapala).- Students stood on the terrace of the Terra Nova Institute demanding the respect that is due them from a society that has owed them since the beginning of time.

Student, Julieta Ortega spoke of the cases of Renata from Oaxaca, Karina from Chiapas and a 14-year-old girl from Jalisco who were all victims of femicide.

«What fear, what rage, what terror! I am sick of living in a place from which I leave my home, but to return is a privilege. I leave with little hope of returning — not only me, but my friends, my teachers, my mother and my sister,» said the outraged high school student.

The young woman shared the results of a 2021 report where the national authorities reviewed 275 cases of femicide and macho violence examining the reason for the irrational hatred of one gender towards the other. Forty-eight percent of the aggressors committed violence because the victim did not want to have sex, and the other 52 percent because the woman disobeyed. This type of violence against women afflicts all 32 states of Mexico.

Julieta reflected: «they are killing us for being women, and every day we suffer intimidation, harassment, threats, resignation, silence and fear.» She said these are reasons not to “celebrate” International Women’s Day but to march to be respected, valued, heard, and to fight against hatred, violence, lack of equity and justice towards the female gender.

«If they kill me and if they find me, this body marked by violence will be the hands that remove the blindfold from people’s eyes. And if they kill me and if they find me, may my death give strength to raise my voice, to remove the ropes from the mouths of my sisters who are still there,» were the poetic words with which Julieta concluded her message.

Terranova Institute celebrated International Women’s Day with conferences, reflections and denunciations from its students.Also present at the meeting were special guests Anabel Lechuga and Erika de la Cerda. The photographer, María Di Paola, gave a presentation of the history of achievements and examples of courageous women whose contribution and sacrifice have allowed us to reach the moment we live in.

Translated by Nita Rudy

Women demonstrate against abuse in Chapala

The march for women’s rights in Chapala advanced with the cry «The oppressor state is a male rapist.» Even children participated in the march.

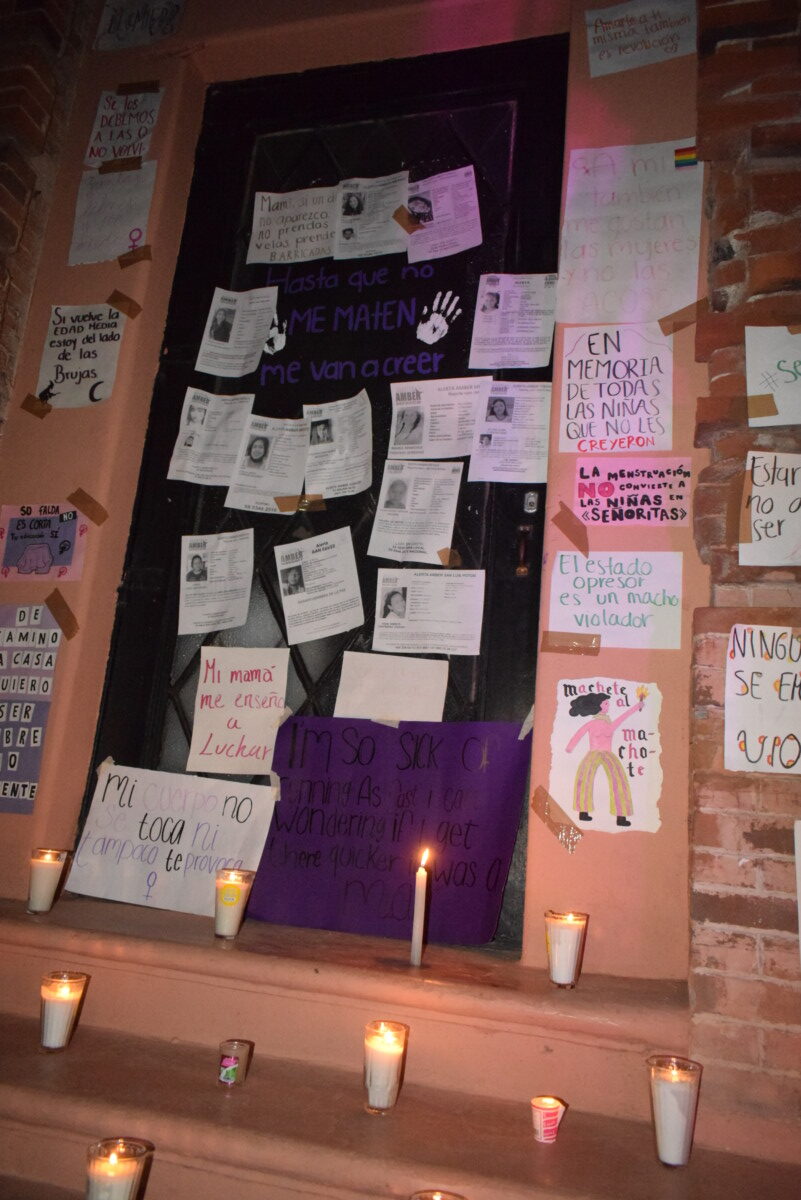

Jazmín Stengel (Chapala).– More than 200 women who demonstrated on Tuesday, March 8, International Women’s Day, used the facade of the Chapala City Hall as a forum to expose the children of former public officials, teachers, among other aggressors of women in the municipality.

The march began after 8:00 p.m. and proceeded along Francisco I. Madero Avenue. Protesters closed the road at the intersection with Morelos Street and Hidalgo Avenue for a little more than ten minutes, and then went to the front of the City Hall. Posters with feminist messages had been pasted on its façade starting two days earlier.

The government was publicly accused of covering up cases of abuse in the municipality: «I am here for those that my municipality wants to erase and silence. No more impunity!» said the protester.

There, different women, especially young women, spoke of cases of harassment, rape and violence committed by the children of former public officials, current public officials, teachers and private individuals, in order to publicize the names and thus avoid further harm to women.

«As long as there is no justice for the people there will be no peace for the government,» declared one of the signs of the young women protesters who on more than one occasion accused the government of protecting the aggressors. They also claimed they were ignored by the authorities when they filed complaints with the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Children also expressed the desire for a better future, «I don’t want to grow up with fear» and «I will be the woman I want to be,» they said during the demonstration.

«I am here for those that my municipality wants to erase and silence. No more impunity!» and «What does a country that sows bodies reap?» read among some of the signs carried by the protesters.

«We are the cry of those who have no voice» said another poster, referring to the 13 women who have disappeared in our municipality. An altar for these women was placed in a door to the building with the message «Sorry for the inconvenience, they are killing us.”

Tears accompanied the confessions; some told their stories for the first time.

Amid tears and shouts of encouragement such as «you are not alone» and «I believe you,» the women who dared to speak out told the tragic stories of the abuses they have suffered. Those who did not speak publicly shared their stories anonymously on the Instagram group @Isonomia.chapala.

The most important issues besides the accusations were the freedom to dress as they please and the insecurity to which women are exposed. «The length of my skirt does not define the respect I deserve,» wrote a protester. Signs read «Quiet mom today I’m not going home alone» and «I can’t die yet.»

Peace and life were the main demands of the demonstration to the government: «What does a country reap when it sows bodies?”

Women were not alone in demanding their rights. Some were accompanied by men carrying with signs that read: «I like women and I don’t harass them.»

The case of Chuyito was also presented. This young boy suffered rape by his stepfather and physical and psychological violence until the day of his death. All women expressed their solidarity with this situation, demanding that the guilty be found and that the case not go unpunished.

Though the march was peaceful, a patrol of the Municipal Police and three state police were present at all times. Traffic police helped drivers who were not part of the demonstration to find an alternate route.

The women expressed their solidarity with Chuyito, a child who died from sexual, physical and psychological abuse. No one has been charged in the crime.

Altar dedicated to the 13 women who disappeared in the municipality of Chapala, titled: «Sorry for the inconvenience, they are killing us.»

Translated by Elisabeth Shields

Lakeside Chronicles

Francisca Lomelí Rodríguez is 96 years old and has retained all her vivid memories that describe the San Cristóbal of her childhood. Photo by: María Reynozo.

By: María del Refugio Reynozo Medina

Francisca Lomelí was orphaned at the age of eight. School was her life. In the San Cristóbal Zapotitlán of her childhood, classes only went up to third grade. She attended school and she remembers the name of her teacher, Trina.

The school was made of adobe and reed. It was not surrounded by a wall, but by a “wall” of huizaches and nopales (native trees and cactus). In addition to learning how to read, the girls learned how to sew and embroider napkins. They spent a lot of time at school because at noon they went home for lunch and then returned to continue the afternoon’s classes. At the end of the school year, the municipal president, accompanied by the town delegate, would go to see the students’ final work. The teachers would place a sample of the student’s embroidered napkins on display.

Corporal punishment was given by wooden ruler. When students did not finish their homework, they were given a few slaps of the ruler.

The teacher wrote lessons in chalk on a blackboard, using a cloth as an eraser. There were no notebooks. The students would buy a sheet of brown paper and tear it into four parts, and when the pages were worn out on both sides, they would buy another sheet.

Francisca remembers the delegate of that time, Beatriz Chavez’s father. He used to openly carry a gun every day. He was a man who was respected. He paid to have a cobblestone pavement installed in town. Despite looking different today, the plaza was the place to go for prominades and serenades.

Chica, as Francisca is known to the townspeople, remembers the nights of music and the women and men milling around. Some women would carry a “chiquihuite” or palm basket with flowers from their garden and sell them for pennies. It used to be very common for there to be fights on holidays. Men would go around armed with guns or knives. Sometimes as many as three or four people were killed, who were left lying around while the aggressor escaped, as there were no police as there are now. The police, who sometimes appeared, were called «Los Charros» by the people.

The women were guarded carefully by their male siblings and parents, although some, when there were weddings, carried a bottle of punch and danced to the music of the harp.

-We waltzed,» they would say.

Chica remembers “El Vapor,” which was a very large boat that came from Chapala. In the morning, very early, it arrived for the passengers and returned in the afternoon. On its journey over the waves of the waters of Chapala, El Vapor, emitted a high-pitched noise that reached the ears of the locals. It was a strange noise, like in the famous song «La Llorona,» the locals said.

People would come to the shore in the morning to say goodbye to their relatives and watch the boat floating in the water, until it was gone from view. In the afternoon, they would also come to the shore to receive the passengers, who came loaded with packages from errands in Chapala.

The steamboat was the only way out, since there was no highway around the lake in those times. The first streets that were made were called caminos. Everything was surrounded by mountains, so it was difficult traveling over them.

In town of San Cristobal, there was not much to buy. There was a store owned by Arnulfo and Lola Aceves. Everything could be bought by centavos: a centavo of butter, a centavo of salt, a centavo of cheese.

Another man was called Tacho. He sold meat, but not every day. When he was going to slaughter an animal, he would announce himself by standing in the middle of the street rubbing his knives against each other. The sound could be heard for many blocks and people knew that there would be fresh meat that day.

“Tacho is sharpening his knives,» people would think, and they would prepare to go shopping. Pigs and chickens were raised in the houses. On special days people would slaughter the pigs that they had raised. Chica remembers the whiteness of the lard and the smell of pork rinds from the houses, as there is no other smell like it. The pigs roamed the streets and none of them got lost. They could roam all day long and return home in the evening to sleep. Sometimes the sows were heavily pregnant and returned home, accompanied by the piglets walking alongside their mother. The chickens were also on the loose, going to and from their homes.

The water of the lagoon was so clean that the people could drink it. The townspeople went with pitchers to bring it back in order to prepare food and also to drink. Chica remembers that her grandfather had some beehives and extracted a lot of honey from them. He would invite the neighbors to bring a small pot to share his honey with them.

There was an «old boy» (that’s what they called him because he never married), but he was a older man. He sold bread in town.

The church was an old building, made of adobe and tile. Father Prisciliano Michel contributed to its improvement. Chica remembers, when she was a child, that after mass they would bring sand from the cemetery. Everyone cooperated, young and old, with whatever they could, and if they could bring a brick, they contributed.

The villagers contributed to the construction of the temple. There was a lot of religious fervor during Holy Week, remember that the women only made hats until Wednesday because Thursday, Friday and Saturday were days of mourning and fasting. The images hanging on the walls were covered with purple cloth as a sign of mourning. No music was played, and many went to church on their knees in the street. Nor did people ride horses; if they passed a cross, they crossed themselves with reverence and the men took off their hats.

In the town there was no Health Center; Daniel Cervantes was everyone’s doctor, he gave injections, he was very good at curing people. Then a doctor Ureña started to come, and another one was called Dr. Cuervo.

From her bed, Francisca continues talking about her childhood and youth.

It was nice,» she says with a smile.

When I ask her about her husband, she says:

“He was my first and last boyfriend.”

José Reynoso and she never talked, they shortened the distance with messages sent through friends, or with José’s whistles from the street informing her that he had been near. On some occasions her friend Margarita Solano, warned her.

-Chirin, chirin!

She would exclaim from the door and Chica would come out to greet her and raise her hand, while behind her friend’s back, Jose would return her greeting from a distance.

Translated by Colleen Beery

OPINIÓN: EL GRITO EN LA LAGUNA

Lago de Chapala. Foto: Héctor Ruiz.

Por: Daniel Jiménez Carranza

La información sin duda, es y ha sido un elemento esencial para la cultura y la adecuada toma de decisiones en cualquier actividad humana; en nuestro país, en la época prehispánica, existían los Códices en donde se reproducían con pinturas vegetales, los hechos relevantes de la época en pieles de animales, hojas de henequén o de amate,; la comunicación entre lugares distantes, la enlazaban a través de un sistema de “postas” que realizaban “los Paynanis”, “Chasquis”, y los “Icluchcatitlantis”, corredores entrenados, que operaban a semejanza de la carrera de relevos, en donde existían postas o albergues llamadas “Techialoyan”, situadas a una distancia promedio de 10 kms. entre una y otra en donde se llevaban a cabo los relevos, pues en América, previo a la llegada de los españoles, no existían caballos, en esta forma, fue como Moctezuma se enteró de la llegada de los españoles; posteriormente en la época de la conquista, continuó utilizándose este medio de comunicación, viéndose complementado con los Pregoneros, quienes se instalaban en plazas o sitios importantes anunciándose con pífanos y tambores para informar sobre fiestas, procesiones, venta de sus productos, o comunicaciones del gobierno virreinal,

Ya en la época de Independencia, la importancia del periódico y el correo jugaron un papel determinante en la consumación de este movimiento. Miguel Hidalgo fundó el periódico “El Despertador Americano” que le permitió propagar su ideario insurgente, así como dar a conocer los abusos del poder español en nuestras tierras.

De esta manera el sistema de comunicación inició su desarrollo en nuestro país, pasando por el telégrafo, la radio, sin olvidar los corridos, género musical de México, que difundía historia de personajes míticos o reales cuya relevancia en la época de la Revolución consistía en relatar los hallazgos y aventuras de sus líderes, llegando así hasta nuestros días, con el acceso a una multiplicidad de escenarios, gracias a la tecnología de internet, que ha ampliado hacia el infinito la expresión de contenidos, en donde la participación se ha desbordado en manifestaciones disonantes donde algunas de ellas llegan a expresar primitivos embates de todo tipo hacia la razón, paralelamente también, existe el acceso a espacios altamente reivindicativos de la cultura y el conocimiento, en donde el consumidor de toda esta información, puede llegar a perderse, particularmente niños o jóvenes cuando no cuentan con un adecuado criterio o formación sólida y ética que les permita realizar una saludable selección de los contenidos.

En suma, es de vital importancia, poder distinguir el contenido de la información entre las noticias, y los comentarios, que representan el punto de vista de quien escribe, distinguir el contenido que alimente el espíritu y no que horade y denigre nuestra persona. Todo ello depende de la decisión del receptor / lector.

Francisca Lomelí Rodríguez: memorias de una mujer casi centenaria

Francisca Lomelí Rodríguez tiene 96 años y todos sus recuerdos vivos que dibujan el San Cristóbal de su infancia. Foto: María Reynozo.

María del Refugio Reynozo Medina .- Francisca Lomelí quedó huérfana a los ocho años. La vida fue su escuela; en el San Cristóbal Zapotitlán de su infancia, las clases llegaban hasta tercero de primaria, ella asistió; recuerda el nombre de su maestra, se llamaba Trina.

La escuela era de adobe y carrizo, no estaba rodeada por un muro sino por un monte lleno de huizaches y nopales. Además de leer, las niñas aprendían a hacer costuras, bordaban servilletas y transcurrían mucho tiempo en la escuela, pues al medio día iban a comer a casa y volvían para continuar la jornada de clases. Para el fin de ciclo escolar, el presidente municipal iba a ver los trabajos finales acompañado del delegado del pueblo; sus maestras colocaban como galería una muestra de las servilletas para la exhibición.

La disciplina se aplicaba con una regla de madera, cuando no terminaban con las tareas les daban unos cuantos reglazos.

En el salón, había una pizarra negra donde la maestra daba las lecciones con la tiza y una tela como borrador. No había cuadernos, les compraban un pliego de papel estraza y lo partían en cuatro partes, cuando las páginas estaban gastadas por ambos lados, compraban otra hoja.

La plaza era solo un espacio parejo de tierra, Francisca recuerda al delegado de entonces, era el papá de Beatriz Chávez; diario traía pistola, era un hombre que se respetaba. Él mandó hacer un empedrado. Aún sin la forma que hoy tiene la plaza, en aquel entonces era el lugar para la reunión de las serenatas.

Chica, como es conocida por los vecinos del pueblo, recuerda las noches de música y las mujeres y hombres dando vueltas. Algunas mujeres llevaban un chiquihuite con flores de su jardín y las vendían a centavo. Antes era muy común que hubiera pleitos en los días de fiesta, los hombres andaban armados con pistola o con navajas. A veces resultaban hasta tres o cuatro muertos, que quedaban tirados mientras que el agresor escapaba, no había policía como ahora. A la policía, que a veces comparecía, la gente les decía los charros.

Las mujeres tenían una vigilancia muy rigurosa por parte de sus hermanos varones y padres, aunque algunas, cuando había bodas, llevaban una botella de ponche y bailaban con el arpa.

-Anduvimos valsando- decían.

Chica recuerda El vapor, que era una lancha muy grande que venía de Chapala. En la mañana, muy temprano, llegaba por los pasajeros y regresaba en la tarde. En su recorrido sobre las olas de las aguas de Chapala, El Vapor, emitía un ruido agudo que llegaba a los oídos de los lugareños. Era un ruido extraño, como la llorona, decían los pobladores.

La gente se acercaba a la orilla en la mañana para despedir a sus familiares y ver flotando en el agua la lancha, hasta que se perdía. En la tarde, también acudían a la orilla para recibir a los pasajeros que venían cargados de mandado que traían de Chapala.

El vapor era la única vía para salir, pues no había carretera aún; a las primeras calles que se formaron les decían camino. Todo estaba rodeado de monte.

En el pueblo, no había mucho donde comprar; había una tienda de un señor llamado Arnulfo y Lola Aceves, todo se podía comprar por un centavo. Un centavo de manteca, un centavo de sal, de queso.

Tacho le decían a otro señor, él vendía carne, pero no todos los días; cuando iba a matar se anunciaba parándose a media calle restregando los cuchillos, uno con otro. El sonido se escuchaba a muchas cuadras y la gente sabía que ese día habría carne fresca.

-Tacho ya está tronando los cuchillos- y preparaban sus platos para ir a comprar. En las casas se criaban puercos y gallinas. En días especiales las personas mataban a sus puercos que habían criado por mucho tiempo; Chica recuerda la blancura de la manteca y el olor a chicharrones de las casas como ya no hay otro igual. Los puercos andaban por las calles y ninguno se perdía, podían andar durante todo el día merodeando y volver caída la tarde a dormir a casa. A veces las puercas iban cargadas con sus crías en el vientre y regresaban acompañadas con los cerditos caminando. También los pollos andaban sueltos, iban y volvían a su casa.

El agua de la laguna era tan limpia que podía beberse, iban con cántaros a traerla para preparar la comida y para tomar. Recuerda que su abuelo tenía unas colmenas y sacaba mucha miel, salía por su puerta de golpe para invitar a los vecinos que trajeran una ollita para darles tacos de miel.

Había un “muchacho viejo” así le decían porque no se casó, pero era señorito. Él vendía pan.

El templo era una construcción viejita, de adobe y teja, hasta había alicantes alrededor y tecolotes merodeando.

El padre Prisciliano Michel, contribuyó a su mejora.

Recuerda Chica, cuando niña, que saliendo de misa iban a traer arena del rumbo del panteón. Todos cooperaban, chicos y grandes, con lo que podían, si se podía llevar un ladrillo, eso se aportaba. También trabajaron el soyate para hacer la trenza, el chicote, copa, ribete, falda y forro, que eran las partes para armar sombreros.

Los pobladores contribuyeron para la construcción del templo. Había mucho fervor religioso, durante la Semana Santa, recuerda que las mujeres solo torteaban hasta el miércoles porque el jueves, viernes y sábado eran días de guardar luto y se ayunaba. Las imágenes que colgaban de las paredes se cubrían con alguna tela morada en señal de duelo. No se escuchaba música, y muchos acudían al templo avanzando de rodillas por la calle. Tampoco se montaba a caballo, si se encontraba uno con una cruz, se persignaba con reverencia y los hombres se sacaban el sombrero.

En el pueblo no había Centro de Salud; Daniel Cervantes era el médico de todos, ponía inyecciones, era muy bueno para curar. Luego ya empezó a venir un doctor Ureña, y el doctor Cuervo le decían a otro.

Desde su cama; Francisca, sigue conversando de sus días de infancia y juventud.

- Era bonito- dice con una sonrisa.

Cuando le pregunto de su esposo, dice:

-Fue mi primero y último novio-

José Reynoso y ella, nunca platicaron, acortaron la distancia con recaditos que se mandaban a través de amigos, o con chiflidos por parte de José desde la calle que le informaban que había estado cerca. En algunas ocasiones su amiga Margarita Solano, le avisaba.

-¡Chirin, chirin!

Exclamaba, desde la puerta y Chica salía a saludarla y levantaba la mano, mientras a espaldas de su amiga, José le regresaba el saludo a distancia.

Luego se metían corriendo para no ser descubiertas.

-Dicen que me parezco a mi abuela Heliodora- me dice Chica que no se cansa de contar.

Yo no sé cómo era Heliodora, pero lo cierto es que Chica tiene unos ojitos vivaces que me recuerdan a mi abuelo, sobre un rostro encendido labrado de arrugas que cuentan mucho.

Sus añoranzas están vivas y dibujan el pueblo que fue, aunque ya no pueda recorrer caminando los patios que de joven convirtió en veredas floridas.

Lakeside Chronicles: The sayaco is the inner child

Front wall of the Romero Pérez brothers’ home is illustrated by masked Sayacos, created by Aarón, one of the brothers. Photo by: María del Refugio Reynozo Medina

María del Refugio Reynozo Medina (Ajijic).- José de Jesús Romero Pérez still has the first hermit-like sayaco mask he made 15 years ago. The dark brown, immobile, sharp face is made of copal, a wood that he brought from the hills. The hollows of the eyes and the slightly open mouth are decayed. The eyebrows, beard and straw-colored mustache are made of a fiber obtained from coffee sacks.

Making a mask can take José de Jesús about two and a half weeks, working in the afternoons after his usual workday. Although he does not make them for commercial purposes, the unique masks which bear his signature, can sell for up to three thousand pesos. The masks that depict women (sayacas) are colorful, with embossed or painted eyelashes and eyelids splashed with glitter. Once carved with a chisel, vinyl paint is used to outline the eyebrows, eyes and eyelashes. The lips and cheekbones are painted deep red circles.

Abel and José de Jesús Romero Pérez grew up watching the sayacos and chasing them in many celebrations. Photo by: María del Refugio Reynozo Medina

The male masks of the sayacos are made of natural light or brown wood, with long beards, bushy eyebrows and moustaches made of horsehair. Romero Pérez’s masks are instantly recognizable. The images flow, as he chisels each feature. A face will emerge unexpectedly from the wood. He knows perfectly well the type of wood needed to design each face. In addition to wood from the native copal tree, he uses native tecomaca wood, which is soft and light.

He has sold eight masks. Buyers do not necessarily wear them in parades. They are purchased by collectors as unique pieces, inspired by the sayacos.

The Romero Pérez brothers Abel, José de Jesús, Gaspar, José, Aarón and Modesto, each year transform themselves into sayacos mainly to inaugurate the carnival. They also attend other celebrations throughout the year.

On a wall outside their home there is an unfinished mural painting drawn by Aarón. The image shows a dancing female sayaca dancing wearing a yellow dress trimmed with colored ribbon and brown booties, accompanied by two male sayacos. One is dancing wearing a brown jacket, denim pants and booties. The other sayaco has a black dress with white dowels as buttons. All of them have long faces, although their appearance in the parades brings smiles and laughter.

With copal or tecomaca wood, the masks made by Jesús Romero are unique pieces. Photo by: María del Refugio Reynozo Medina

“The sayaco is a very old character in the life of the people of Ajijic”, says Abel. They used to be called sayacal. Now they are called sayacas and sayacos. It is that mocking character that appears mainly in the carnival. They throw confetti and sometimes flour. Sometimes the flour is delicately smeared on their cheeks.

One of the main dances of the sayacos is called the dance of the «papaqui» which is accompanied by wind instruments. Sometimes they are invited to perform their dances at weddings or quinceañeras, the celebration of a girl’s 15th birthday. Abel remembers as a child watching the sayacos in the daily festivities. He and his siblings would race through the cobblestone streets following and teasing the sayacos amidst happy laughter.

The masks of Jesus Romero Perez stamped with his signature can be worth up to three thousand pesos. Photo by: María del Refugio Reynozo Medina

The carnival parade is open to the entire population and a diversity of characters appear. The traditional attire is wooden or papier-mâché masks, sacks, shirts with dowels, booties, and hats. The sayacas wear bright printed dresses.

There is pride in being a sayaco. It is a nice, mocking, very old character who makes people laugh. The sayacos are mainly men. Even the sayacas are usually men because of the pushing, shoving, brawling atmosphere.

The first mask made by José de Jesús Romero Pérez was of a hermit in copal wood. photo by: María del Refugio Reynozo Medina

Behind the masks of tough men or picturesque red-cheeked women are the Romero Perez brothers. They appear in the parades and processions so that the legendary figures of the sayacos do not die and because Abel says «behind the wooden masks is the inner child.»

Translated by Nita Rudy

© 2016. Todos los derechos reservados. Semanario de la Ribera de Chapala